The Human Body is Naturally Asymmetrical

At first glance, we may notice our bodies’ symmetry — two eyes, two ears, two arms, two legs, and paired muscles on both sides. When working out, we intuitively avoid strengthening just one side to prevent feeling imbalanced afterwards. However, if we take a closer look, it quickly becomes apparent that we overestimate this symmetry. Most of us are not perfectly symmetrical and do not use our bodies evenly.

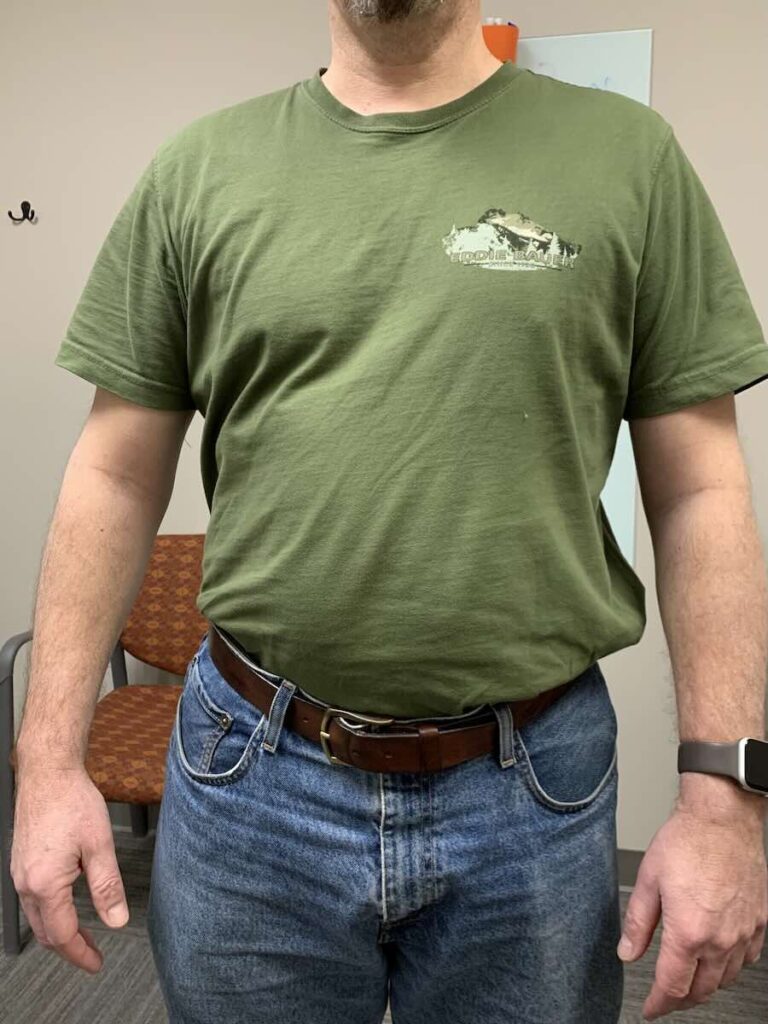

Asymmetry is visible throughout our bodies. Shoulders may be uneven heights, spines curved, faces lopsided with one eye higher than the other, heads tilted on upright bodies, feet turned outward, and pants twisted. People often stand and move awkwardly, with deviated septums, crooked teeth, or perfectly aligned teeth on crooked faces. Observing movement can reveal more asymmetries: arms swinging differently, bodies shifting easily to one side but not crossing the midline to the other, lateral pelvic tilt or hip drop, heel whips, and feet hitting the ground with different sounds. What causes these postural and movement asymmetries? Our handedness (being left or right handed) surely plays a role in developing them over time. However, a look beneath the skin reveals intrinsic clues. Our asymmetrical bodies and movement patterns arise from a combination of environmental factors and inherent biological ones.

Our brains, muscles, cardiovascular system, eyes, lungs, and several organs are asymmetrical by nature, having been that way since birth. Remarkably, our bodies balance these innate asymmetries, enabling us to perform actions like walking without conscious effort and to remain upright despite an off-center center of gravity. Though our bodies naturally integrate systems to achieve balance, certain functions show a right-side dominance. Our jobs, hobbies, and lifestyles can reinforce this one-sidedness until dysfunctional, lateralized movement patterns take over.

Over Time, Dysfunctional Movement Patterns Can Cause Issues

When our bodies move in harmony, we function like a well-oiled machine. Our muscles engage and relax with precise timing, allowing us to maintain balance and align our heads over our bodies. This gives us accurate sensory information about our surroundings. Our arms and legs swing in alternation, propelling us forward. Meanwhile, our core twists and pumps to support our organs and enable efficient breathing during movement. The forces on our joints distribute evenly as our skeletal structure supports our center of mass where balance is centered, keeping us stable. Pressure sensors throughout the body, together with visual and vestibular senses, give our brains a comprehensive understanding of our body’s position. We remain safe with an agile, responsive nervous system. The intricacy of human movement and the internal coordination enabling it are truly remarkable.

Unfortunately, for most of us, this delicate balance is disrupted early on as we develop a dominant side. Muscles may stay activated when it is their time to rest, while others struggle to engage. This leads to overuse injuries and impaired muscle function. The ideal length-tension relationship for muscles becomes compromised. Once supported by proper skeletal alignment, our bodies now rely more on ligaments, joint capsules, and our overused muscles for stability. This leads to issues like hypermobility, instability, tears, degeneration, and more. The dynamic work of our breathing and pelvic diaphragms now fails to maintain optimal core pressure. Support is lost for the abdominal organs and posture suffers. Head alignment over the body becomes difficult. Soon the brain and nervous system become threatened by the compromise. The autonomic nervous system becomes overly sympathetic.

Injuries Can Also Produce Body Asymmetry

In addition to internal anatomical factors that cause predictable asymmetry, external factors like injury, disease, and congenital abnormalities can also produce or worsen body asymmetry. For example, recurrent ankle sprain or foot injury can cause a shift in weight acceptance tolerated for walking and change how we stack ourselves up over the foot we choose. Just as much, a long rehab from a shoulder surgery may diminish arm swing and trunk rotation on one side. A true leg length discrepancy alters pelvis orientation and forces compensatory movement patterns that increase asymmetry. Rib injuries, laparoscopic procedures, gut inflammation, and even pregnancy can impair proper breathing posture, requiring us to find alternate postural and movement strategies to maintain balance and airflow.

Body Asymmetry Can Cause Problems

Body asymmetry is completely normal and can be attributed to multiple body systems. Appropriately managing these asymmetries is essential. Our brains automatically orient our bodies to maintain airflow, stabilize our heads during movement so our eyes can provide real-time environmental information, and protect us from falling. Although this survival drive is necessary and complex, it may also cause us to adopt compensations — movement strategies that accomplish the goal but strain other body systems.

Dominant movement patterns emerge when body asymmetry and imbalance are not integrated through reciprocal walking and breathing. Dominant movement patterns are likely to develop as our brain receives different visual information from the left and right eye. We have non-paired organs of different weights and sizes. We live in a world that favors movements towards one side over the other. As these differences are reinforced over time, common orthopedic issues can develop like muscle overuse, instability, weakness, and compensation.

As one side becomes dominant and stronger, our compensation strategies create a new normal for movement. Over time, some muscles bear excessive burden, tightening unevenly, while others weaken from underuse. The result is a body adapted to suboptimal movement strategies.

Movement Patterns

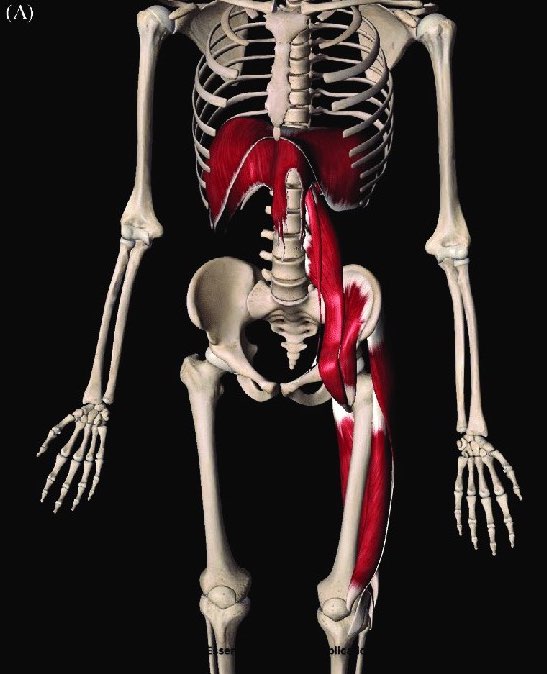

PRI identifies several muscle chains that are paired on both sides of the body. As we develop a dominant side, an asymmetrical movement pattern emerges. In the common pattern PRI teaches, the left Anterior Interior Chain (AIC), right Brachial Chain (BC), and right TemporoMandibular Cervical Chain (TMCC) become dominant and activate appropriately during right stance (see images above). However, the opposing chains (right AIC, left BC, left TMCC) remain inhibited even as weight shifts left. Thus, the right stance muscles stay active during both left and right stance phases of gait.

Hyperflexibility or Hypoflexibility

Understanding appropriate joint flexibility requires examining the whole body and the demands placed on the joint. Consider two people with forward-tipped pelvises when asked to touch their toes. Person A cannot reach their fingers remotely close to their toes and says, “I’ve always been tight my whole life!” Person B eagerly touches the floor stating “I’ve always been flexible”. Although it is easy to assume Person B has good flexibility and that Person A needs to stretch their tight hamstrings and back, Person A has appropriate flexibility for their pattern. The forward pelvis pre-stretches hamstrings, reaching end range sooner when bending. Assuming Person B has excessive flexibility will cause them to miss their true need — restoring proper pelvic position and hamstring function.

Muscle Imbalance

Like ropes on either side of a pulley, muscles work in coordinated pairs. When one muscle contracts, the opposing muscle must lengthen to allow proper joint movement. This coordination enables smooth, balanced motion. Imbalances occur when a muscle has trouble contracting or relaxing. When one muscle in the pair can not pull well, or another muscle can not “let go” well, the result is called a muscle imbalance. For example, the biceps and triceps control elbow bending and straightening. If the biceps stay tight and the triceps are weak, an imbalance develops and the elbow joint can’t move freely. Identifying and addressing these imbalances can improve joint function. Often, muscles that have difficulty relaxing are being called to work by the body for non-orthopedic reasons.

Common Body Asymmetries

Human posture has been studied for centuries and consistent patterns of asymmetry have been identified for as long. These common body asymmetries all have tests that a postural therapist can perform to identify likely causes and direction for change. Without this, asymmetry can be like chasing the chicken vs the egg question. Is the left shoulder high or the right shoulder low? Is the left hip forward or the right hip backward? Below are a few of the areas we look closely at:

Uneven Shoulders / One Shoulder Higher Than the Other

A common asymmetry of the body that can be easily spotted even by the casual observer is uneven shoulder height. Uneven shoulders are not a problem but a symptom of an underlying breathing imbalance that results from normal human asymmetry of the body. This asymmetry can be seen in the size and position of our organs, and especially the shape and strength of our diaphragms. These asymmetries cause us to orient to our right side in the same way we shift our weight to the right during gait. When we are there, the right side of the diaphragm is positioned to be a better pump, pulling air into the elevated and larger left chest wall. This orientation to the right in most human beings is the cause of a shoulder that may lower on the right than the left.

Although it is common to see a lower right shoulder as we orient to our right side, as we repeat this pattern over time, our bodies begin to find compensations to allow us to be able to center our asymmetric selves in an effort to alternate to either side. The internal threat that arises from our inability to manage airflow to our right chest when in the left stance (due to a right side dominant movement pattern that fails to shut off when we go to the left) could lead to a dropping of the left shoulder in order to improve right chest expansion. This is one reason you may see a lower left shoulder instead of a right.

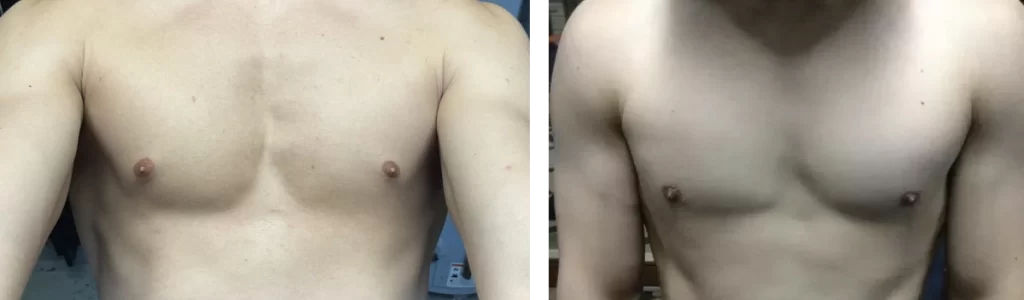

Uneven Chest or Pecs

Like other instances of uneven left and right sided muscle development that result from patterned movement asymmetry, predictable differences in the chest or pecs can also be observed. Although differences in functional demand can cause muscle development to differ between sides, the fullness of the chest can also be a reflection of the position of the ribcage underneath. For example in the common right lateralized individual you will often see a lower right shoulder which occurs as the upper thorax rotates left to center the body over a pelvis and lumbar spine that is rotated to the right. This motion of the thoracic spine contributes to compression on the right side, as well as internal rotation of the right rib cage and expansion in the left upper rib cage. This position dictates that the best place to put air while attempting to inhale from this position is into the left upper rib cage. Thus the fullness that can be observed in the left chest relative to the right can be a reflection of rib expansion due to biased airflow into this space.

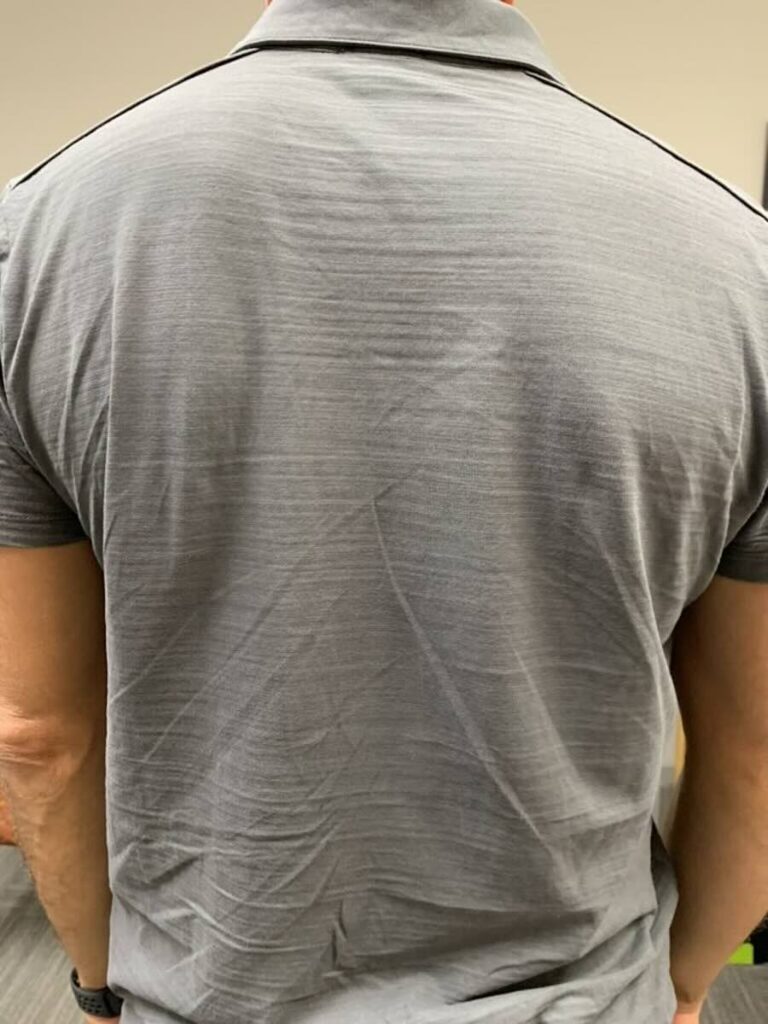

Uneven Rib Cage

The rib cage is formed by the thoracic vertebrae, ribs, costal cartilage, and sternum and offers protection to the organs within the thoracic cavity, assistance for breathing, and support of the upper extremities. This interconnectedness means that any movement of the spine will be coupled with movement of the ribs that attach to it. Due to human asymmetry, deviations from normal spinal curvature will occur. In the thoracic spine, when there is a sidebending movement that occurs, it will be coupled with rotation of the spine and ribs. This can cause visible rib humps to emerge and this expansion of the rib cage becomes a low-pressure area where it becomes easier to move air during inhalation. In a typical right lateralized person it is common to observe fullness in the left chest relative to the right, as well as fullness in the right mid back relative to the left.

Uneven Hips or Pelvis

Uneven hips, also known as “lateral pelvic tilt” or “hip hike” is a posture where one hip sits higher or lower than the other and is a common occurrence seen in leg length discrepancies, hip muscle imbalance, dominant movement patterns, and uneven respiration. Uneven hips are likely to be found alongside lateral curvature of the spine and uneven shoulder height.

Leg Length Differences

Although true leg length differences (LLD) do occur, such as those that are congenital or result from surgery, they are much less common than functional leg length differences. In pelvic asymmetry, the mere presence of unevenness between the two sides of the pelvis will cause observation differences in how the length of the legs compare. Many healthcare providers will perform cursory visual assessments of leg length, but be cautioned that these observations and even x-ray of the legs are not enough to reflect rotational differences or the cause of the difference between the sides. Many postural considerations and tests should be correlated when determining the cause of the apparent LLD and what, if anything, should be done about it.

Common body asymmetries result in a pelvis that is forward on one side. This asymmetry will result in the orientation of the hip socket on the left to be different than that on the right. This causes the femurs to cast off the hip socket at different angles and results in the appearance of asymmetry when observed at the knees, ankles, and feet. The correction for this is rarely a heel lift, or an adjustment to the hips or pelvis.

Uneven Quads or Uneven Hamstrings

Uneven muscle development or hypertrophy of muscle can be observed when one side of the body is clearly using more of the capacity of the muscle and is a sign of imbalance or dominant postures. While some believe that muscle definition is desired, often we see measurable differences between the two sides, or favoring one muscle of a balanced pair. In the case of a left quad vs a right quad, we often see the large lateral quad (vastus lateralis) being overused in the presence of hip rotational weakness to direct the femur in line with foot while the asymmetrical pelvis is oriented more to one side. Often, when both quads are overdeveloped, there is anterior pelvic tilt and hip flexion that is overworking muscles of knee extension and back extension. In order for proper hamstring and quadricep balance to be appreciated, the pelvis must be able to posterior tilt while hip extension is taking place. This is optimal during the stance phase of gait where the hamstrings are actively anchoring the pelvis in a PPT while the leg travels under the body. If there is anterior pelvic positioning in the stance phase, the flexed hip position will inhibit the hamstrings, and more work will be placed on the quads for knee extension while the hip is flexed.

Muscle imbalances or hypertrophy on one side of the body often indicate dominant postures or overuse of certain muscles. While some view pronounced muscles as desirable, noticeable size differences between sides or in paired muscles frequently signify imbalance. For example, overuse of the large outer quadriceps muscle (vastus lateralis) on one leg can occur to compensate for hip weakness and improperly align the thigh with the foot if the pelvis is asymmetrical. Overdeveloped quadriceps on both sides usually coincide with excessive anterior pelvic tilt and hip flexion that overwork the knee extensors and back extensors. For the quadriceps and hamstrings to function optimally, the pelvis must be able to tilt posteriorly during hip extension, as occurs ideally during the stance phase of walking when the hamstrings actively anchor the pelvis in a posterior tilt as the leg moves under the body. If anterior pelvic tilt persists during stance phase, the flexed hip position will inhibit the hamstrings, increasing reliance on the quadriceps for knee extension with the hip flexed.

Uneven Calf Muscles

It is common to see differences in the way the left and right calf muscles develop, and for a lot of individuals the right calf muscle will be larger than the left. This difference in calf development reflects a difference in functional demands between the left and right sides. Human asymmetry drives asymmetrical movement patterns that cause overactivity in certain muscle groups and inhibition of others. The overdevelopment of the calf muscle is often driven by increased demand on the extension/rotation of the propulsive limb (stance phase) in the presence of extension weakness or imbalance. When the body needs push off and rotate toward midline, whatever the body does not acquire from the glutes and hamstrings, it will make up at toe-off via the calf muscles.

Postural Restoration Can Treat Body Asymmetry Issues

Postural Restoration is the study and treatment of patterned human asymmetry. Its tests, methods, and corrective activity serve clients that have tried orthopedic approaches to make changes to body position, flexibility, and strength without lasting results. Often a Certified Postural Restoration Specialist can provide the tests, education, and treatment activities you need to finally get on track. If this describes you, contact us to get started with PRI physical therapy.